FoR3 news items for 2015

-

July 27 2015: Why Alan is right

- We published our opinion some while back on 'Why Roger is wrong': this seems a moment to comment on Radio 3's latest controller, following an article in last week's Guardian.

Davey has made it clear there will be no attempt to compete with Classic FM, which, with its touchy feeliness and "smiling down the airwaves", has almost treble Radio 3's audience. Chasing ratings is a recipe for disaster, he says: audiences can sniff out manipulative programming a mile off. He points out that Radio 3's famously highbrow original incarnation, the Third Programme, will celebrate 70 years since its foundation next year, and he intends to honour its memory. There will be no dumbing down on Davey's watch.Chasing ratings, gaining new listeners. Dumbing down, reaching the broader audience. Every policy has its opposite; and both, it seems, are equally good. But, no, they aren't, not for every context. Let's look at the latest edition (2015) of Fowler's Modern English Usage. Under 'dumbing down' (a new phenomenon since 1926, apparently): 'to make more simple or less intellectually demanding, especially in order to appeal to a broader audience'.

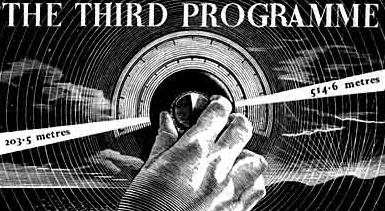

'Make more simple or less intellectually demanding'? That doesn't sound at all like William Haley's idea when he introduced his Third Programme in 1946. He wanted a service which, by being intellectually demanding – and sometimes difficult – would of necessity not appeal to a broader audience. That was its justification, its raison d'être.

As long as there is an audience for such a service, the BBC should not bow to any pressures to downgrade it. Heaven knows! BBC coverage of popular culture/light entertainment, especially on television, has expanded enormously post-1967; so if they want all the goodies of the arts and classical music to be 'for everyone', 'accessible to a broader audience', they should provide the 'simpler, less intellectually demanding' content somewhere else, on television or radio.

What Roger Wright possessed in professional music qualifications, Alan Davey has in – pause to consider words – 'high culture' qualifications:

Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), English Language and Literature, First Class Honours

1979 – 1983, University of Birmingham

Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.), 'An Edition of the shorter Gautreks Saga' (Old Icelandic), 1983 – 1985, Merton College, Oxford

Master of Arts (M.A.), Classical and Ancient Studies, 1995 – 1997, Birkbeck College, University of London

Plus a couple of old honorary doctorates thrown in. And a devotion to classical music.

That's the Third Programme. That's Radio 3. The challenge (at least, one of them) is to acknowledge what currently isn't of Radio 3 standard on the station. And perhaps also point out in high places that the ongoing disagreements about popular culture on Radio 3 and at the Proms is not about denigrating popular culture; it's about the increasing imbalance: less coverage for the arts and 'high culture' (pace Pappano's excellent Classical Voices on BBC Four) and more coverage for light entertainment and popular culture. Promoting the marketable. -

July 11 2015: What a kerfuffle?

- A pre-Proms article in the Radio Times by Radio 3 presenter Suzy Klein caused some bewilderment. It hinged on the supposed 'outcry' at the inclusion of a Radio 1 'dance party' Prom. Yet, apart from a quote from MP Bill Cash (not known as an enthusiastic classical music fan), there seemed to be little evidence of revolting concert-goers.

Here are a few more quibbles with the piece:

1. 'When the Proms season season was announced, some headlines screamed “It's all gone Pete Tong”. I wasn't terribly surprised. What had got the critics worked up …'

A misunderstanding. These were not headlines 'screaming' anything; they were light-hearted, rather witty exploitations of the title of a 10-year-old film of the same name, about a DJ, Ibiza – and with an appearance by Pete Tong. The Daily Telegraph and Daily Express both came up with the same headline, but the stories beneath were not at all critical – they were reporting the new season. As newspapers tend to do, they homed in on the non-classical concerts but can hardly be criticised for that – Suzy Klein's piece does exactly the same, barely a mention of the main concerts; but good publicity for the 'novelties'.

2. 'Of course, turning the Royal Albert Hall into an arena full of dance-crazed ravers was going to ruffle some feathers (and the papers do love a good headline …)'

The headline has already been explained: it did not indicate ruffled feathers, though there was a story in the Daily Mail about Bill Cash MP being less than impressed. However, reading on:

3. 'After all, this is the classical music festival that set out to be as inclusive and broad as possible from its earliest days.'

Up to a point, Ms Klein. In the earliest Proms you may spot the odd song like 'I am the Bandolero', part of a G&S operetta or a soulful Victorian ballad, jostling alongside Wagner or Verdi, but there are two points:

i) there are no concerts devoted entirely to the really popular of the day, say, music hall – no Florrie Forde or Marie Lloyd Prom; no My Old Man Said Follow The Van, Down At The Old Bull And Bush or I'm Enery the Eighth. No sign of Al Bowlly, Rudy Vallée or Whispering Jack Smith among the performers. So the concerts weren't completely musically 'inclusive'.

ii) The major aim of the 'classical music festival' was to 'train' an audience to love classical music. Robert Newman said he wanted: “to train the public in easy stages [...] Popular at first, gradually raising the standard until I have created a public for classical and modern music.” By modern Proms standards, the early concerts were lighter, more 'popular' but they were always substantially 'classical'; and the aim was to lead the public into an appreciation of classical music.

So - without wishing to give the impression of ruffled feathers or being worked up - it seems incorrect to regard a Radio 1 dance party as leading anyone to appreciate classical music. Unless there is a mix of popular and classical the aims of the Proms founders are not being continued. Is there any evidence that such concerts 'engage the audience of tomorrow', other than in giving them what they already know and like?

4. The writer then goes on to lavish fulsome praise upon the rappers of the 1Xtra Prom. “Who says you're not allowed to enjoy all of it?” Well, no-one, actually, though it seems most unlikely that the majority of the dance and rap audiences enjoy 'a Brahms symphony' or the operas of Mozart. Does it? And they're not very likely to discover them if the concert which first attracts them has nothing except 'their kind of music'.

5. But we are assured that 'self-elected snobs' should take a lesson from the Glastonbury audience. No cries of dismay when Glasto welcomed the English National Opera in ... well, 2004 it was – over ten years ago. And there hasn't been even one annual classical concert there since (there are roughly a dozen non-classical concerts at this year's Proms). Furthermore, although the Pyramid holds several tens of thousands of people (by some estimates almost 100,000), rather fewer (about 15,000) are said to have chosen to attend the opera; so the rest of the festival-goers were attending acts on the other stages. Voting with their feet rather than raised voices?

And finally:

6. “ Great music festivals must embrace great music in its many guises” [who decides what is 'great music'?] “ – and the Proms must do more so than any other” [oh? why is that?] . “After all, it's been in the contract since since 1895.” Dan Leno singing “The Hard-Boiled Egg And The Wasp? No, the early Proms certainly had their boundaries.

The main gripe would not be the inclusion of various flavours of popular music, for youth and middle youth: it's the fact that such concerts are yet another no-go area for classical music.

The BBC clearly doesn't have confidence that, when it comes to music, everyone will enjoy all of it. Unlike Robert Newman, it does little to extend the horizons of those unfamiliar with classical music. Though Radio 3 listeners will no doubt be fascinated by the rap and dance… -

June 8 2015: Oh, what a day it was!

- Much of the BBC’s day of music consisted of the appearances of a host of people, drunk with enthusiasm for something called ‘music’. On Radio 3 it was a mixed affair which, with such honourable exceptions as the lunchtime concert and CotW, started from a low-point and followed a downward trajectory to end in beer house revelry.

Given the BBC’s love affair with popular music, a special pan-BBC ‘music day’ was always going to provide meagre pickings for classical and jazz listeners. When Radio 3 is thrown into a melting pot with all the other services - this applied equally to the (now scrapped) Radio Academy Awards - it’s at a disadvantage because organisers, judges, audiences, media, are all focused on the popular/populist - big personalities, big stories, big audiences. Even Radio 3’s most distinguished drama was seldom rewarded when up against Radio 4.

But what devious (or stupid) idea was behind the evening simulcast of Radio 2’s gala edition of Friday Night Is Music Night on Radio 3? What percentage of Radio 3’s evening concert audience was likely to be interested in middle-aged, middle-of-the-road pop? Why would the natural audience not be listening to it on Radio 2?

We pointed out that BBC Four - BBC television’s ‘home of classical music’ - celebrated Music Day with a string of pop programmes. Ordinarily that would not be a matter of huge concern, but on a day when Radio 3 was converted to Radio 2 for the evening, it would have been good to have been able to seek refuge on BBC Four, even for half an hour.

One contributor rhapsodised over music’s power to ‘bring people together’: it can also isolate and depress when listeners hear nothing but other people’s taste in music (and that doesn’t mean Shostakovich rather than Tchaikovsky or Palestrina – it means Deacon Blue or Lulu rather than Shostakovich).

BBC - your music policy has become rubbish. It isn’t just that Radio 3’s budget has been squeezed relative to the other network stations, so that its annual service budget is now the same as Radio 1’s (£40m), with another £46m for Radio 2 and £20m for the digital stations, all providing popular music; it isn’t just the money: think of the difference in terms of airtime - more than five times as much popular music (given that Radio 3’s airtime also covers jazz, world music and arts/speech).

All right. It states the obvious to say ‘most people’ prefer popular music. Does the BBC accept any responsibility for introducing new audiences to other kinds of music? The real irony is that it does. But it still pushes the classical music, (and the serious jazz) on to Radio 3 where it then, unforgivably, popularises the presentation to get a ‘new audience’. In the process it alienates listeners capable of enjoying it without sweeteners and who have higher critical standards.

The BBC stated (2011): “We believe that the BBC has a responsibility for making classical, jazz and world music, as well as other arts and cultural content, available and appealing to all licence fee payers.”

So Radio 2 drops Your Hundred Best Tunes and Melodies for You.

Again, the BBC (2011): “To help promote classical music across the BBC portfolio, BBC management has recently established a classical music board”

“This is chaired by the Controller of Radio 3 and has responsibility for developing and creating cross-platform ideas that will promote this programming across the BBC. The classical music board has representatives from various parts of the BBC who provide classical music output for television, radio, interactive services and the Proms, as well as representatives from marketing, communications and audiences.”

Where is the classical music board now? Who is it promoting classical music ‘across the BBC portfolio’? How does Radio 2 ‘promote classical music’ if it axes Your Hundred Best Tunes and Melodies for You? Does Radio 2 plan to off-load Friday Night Is Music Night on to Radio 3? Perhaps even Desmond Carrington’s The Music Goes Round (that doesn’t have any classical music, but what the hell?).

It seems that Radio 3 can give over its airtime to promote popular music, film music, musical theatre, the Great American Songbook and pointless celebrities week-in, week-out, but where’s the quid pro quo elsewhere, ‘across the BBC portfolio’? -

May 28 2015: Aims and outcomes

- As we have said before, listening figures are unimportant in most ways. It doesn't matter, for instance, that Radio 3's audience is smaller than that of a popular music radio station. But looking at trends is setting Radio 3's performance against itself. Is it doing better now than five years ago? Is it doing less well?

It also matters what the station is trying to achieve (insofar as we, the public, know what that is). Is it succeeding or failing? Is it trying to achieve the right things? In the right way? Do the listening figures help us to understand that?

Last week's RAJAR figures looked like a bit of a yawn - no better and no worse than one would expect. However, after three successive quarters of being humbled by 6 Music, Radio 3 did manage to ease ahead of the digital popular music station, which stumbled a little this time.

The figures for March complete the set for the BBC's financial year 2014-15. Here we can see the legacy inherited by the incoming controller. The year's weekly average doesn't look so good: at 1.9775m, this is the first year since 2008-09 (the dark days following the introduction of Breakfast) that the yearly average has been below 2m.

But there is a bit more to it than that: each quarter the percentage of the population tuning in to Radio 3 is at an unvarying 4%. Except that it isn't really unvarying. It's 4% exactly only because the figure is rounded up or down to the nearest whole figure. So anything between 4.49% and 3.5% will be recorded as 4%. So 4.5% will be 5% and 3.49% will be 3%.

RAJAR introduced its new data collection methodology sixteen years ago. From 1999-2007, the percentage, when calculated exactly, only once (2006-07) fell below 4.0%. From 2007-2015, it has only twice been above 4.0%. But worse than that, for the year 2014-15 the percentage was the lowest since comparable data has been available, the figure being 3.697%. Remember, it has only to drop below 3.5%, and it will be recorded as 3% - for the first time ever. Although the actual reach remains 'stable' at around 2m, the population rises each year.

The other point of interest is the trend of the breakfast programme reach. For this we have three complete years for comparison; that is, since it was shortened to 2 ½ hours. Prior to that it was 3 hours long and no comparison can be made. The average weekly reach for those complete years has been:

2012-13 – 674,500

2013-14 – 590,800

2014-15 – 572,800

It might be observed that reach has declined for a peaktime programme that was designed to attract new listeners. If it was intended to deter regular listeners from listening, it has succeeded. Many of them hate it. They hate the listener contributions, the increased presenter input at the expense of the music, the truncated longer works, the frequent appearance of Copland's Rodeo, Piazzolla's Libertango, Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag, Bernstein's Candide Overture, Gershwin's Girl Crazy/An American in Paris…

And listeners won't be overjoyed at Radio 2's Friday Night Is Music Night being simulcast on Radio 3 as the evening concert (with Bernstein's Candide Overture, as it happens, though it hasn't been on Radio 3 since last Saturday). Couldn't someone with a bit of imagination have put together a Radio 3 concert and simulcast it on Radio 2? Why can't the BBC ask a bit more of Radio 2's listeners for once instead of asking a lot less of Radio 3's listeners most of the time? -

April 13 2015: Tale of two interviews

- The time has been judged right, it appears, for the new Radio 3 controller, Alan Davey, to face the press and sketch out some preliminary ideas of what can be expected of 'his' Radio 3. A double-page spread appeared in the Sunday Times Culture supplement last week (3 April), written by Bryan Appleyard; and, in the new - May - issue of the BBC Music Magazine, an article portentously featured as The James Naughtie Interview (or James Naughtie meets…).

They cover much the same ground, any difference being characterised, on the one hand, by the rapier economy of Appleyard's dismissal of 'opportunistic, philistine MPs who think classical music is, by definition, "elitist" '; and on the other hand, Jim's bumbling ten-line rant against the phrase 'dumbing down', its uselessness, meaninglessness, misleadingness, and the lofty dismissal of those who use it ("it usually means almost nothing, saying more about the person who uses it than the thing described"). Well, yes indeed, Jim, by their insults shalt thou know them. But, as a quid pro quo, if you wouldn't mind eschewing 'conservative' and 'traditionalist' (you forgot 'elitist')… ?

At any rate, Jim assured us that, 'without anything being said', he and his interviewee agreed not to use the phrase 'dumbing down' (did they use sign language, mime, or exchange secret notes to come to this mutual pre-agreement?). It could be noted that, whereas Alan Davey was no doubt perfectly relaxed about the prohibition, as a keen student of matters cultural he will certainly have a very clear idea of what people mean by the phrase; and in other circumstances, would surely relish discussing it, its manifestation in modern culture and even - whisper it not - how it might affect Radio 3.

For Jim's enlightenment, we quote the 2015 edition of Fowler's Modern English Usage: 'meaning 'to make more simple or less demanding, especially in order to appeal to a broader audience' with pejorative connotations' - succinctness Jim would surely envy.

Both articles repeat what is known of Davey's musical background. Neither is concerned to harp on the past or the Wright legacy. Appleyard explores Davey's belief in the general importance of culture and the arts. Musical education is important, developing a future audience. Munrow's Pied Piper is mentioned: young people have more distractions now than in those days but their taste in music is not restricted to 'pop'. He thinks there is nothing to prevent them appreciating classical music, is aware that Radio 3 has a serious mission and his ambition is for the station to do, better, what it does best.

Naughtie's piece is, understandably, more BBC-slanted (perhaps that explains an 'overdefensiveness', the concern to protect, to give likely critics a surreptitious poke in the eye?): previous controllers are recalled, Wright, Kenyon, Drummond, Glock; Radio 3's public 'purpose' is outlined. Many of the same themes emerge, for example, musical education - Antony Hopkins, as well as David Munrow, is mentioned. Outreach.

A good Davey phrase: "No one wants to put up barriers." (Indeed. How tired one becomes of hearing people claim, idiotically: 'They want to keep people out. They want to keep it for themselves.")

A phrase to be careful with: "Trusted guide." That should be a Radio 3 aim, an ambition. But, "They shouldn't need to be told that all the time." And it's the listeners who will decide who is trusted and who isn't. Children may trust their teachers where adults will have a more critical outlook.

Disagree with: the praise for Essential Classics. This has to be Davey's Top Gear dilemma. Yes, it's popular, but its mindnumbing, overgenial, folksiness dominates far too much of the mid-morning schedule. Too much, erm, 'dumbing down'. It would be improved immeasurably by a complete change of format.

Interesting ideas: Opera (ROH) to return to Saturday evenings, with Mondays to be a 'stage for foreign/European orchestras'; more contemporary music throughout the schedule, not just after the world has gone to bed; more about 'how music works', with Talking About Music a model; exploring the BBC archive; presenters can be informal, must be informed (at present some are more informal than informed); perhaps Scandinavian drama, in translation but with the original text online. But why just Scandinavian: why not of Europe, the world, the universe? Bring it on!

Blessed relief: the end of breakfast phone-ins (listeners to Radio 2 envy us!) and the 15-minute repetitions of the morning's headlines. More to come? 'No to tweets' means 'Please don't read them out on air, and limit the number of times listeners are invited to tweet/text/email.' This distracts/detracts from the main business. The Facebook page is now less of a cheap advertising hoarding, more of a reference source. And has there been a deliberate policy to return complete recitals to the lunchtime slot, in place of patchwork compilations? If so, a good, necessary move.

Still plenty to do - but it bodes well so far.

Alan Davey will also be on Radio 4's Feedback programme on Friday 17 April at 4.30pm. -

March 26 2015: Thought for Today

- If Sir William Haley had been told that his Third Programme was sometimes inaccessible, intimidating or daunting to 'some audiences', he would have been satisfied that it was doing its job properly: he did not intend it to be for a generalist audience.

And if Radio 3's audience is 'too white, too middle-class, too old', that isn't Radio 3's responsibility - or fault. The BBC has been pumping popular music into the nation's youth for almost fifty years: it has popular music for young audiences on Radio 1, popular music for older audiences on Radio 2 and 6 Music, youth-oriented popular black music on 1Xtra and popular Asian music on the Asian Network.

Further, plays - 'theatre drama' - have disappeared from television and radio almost entirely. How many people even remember what they were?

Radio 3's arts content is either worth doing, or it's not. If it is, it should be done properly and promoted with confidence and total belief in its worth. For the year 2013-14, Radio 3's 'service budget' was less than Radio 1's, in spite of the substantial financial support Radio 3 gives (and is obliged to give) to two 'brands' which significantly sustain the BBC's cultural reputation: the BBC Performing Groups and the BBC Proms. Where would these (and the BBC) be without Radio 3? Radio 2 carrying all the concerts of the BBC Orchestras? Radio 4 broadcasting all the Proms concerts?

In addition, Radio 3's service licence commits it to producing some of the most expensive programming on radio: long-form drama - the only BBC service, on radio or television, which is committed to providing it. It also provided new, experimental writing, but that can't now be afforded, apparently, in spite of the head of radio declaring to a parliamentary committee that it was 'absolutely critical to the future of new writers in this genre'. The station was expected to do all that on less than the BBC was allowing Radio 1 alone. For the 2014/15, Radio 3 gets exactly the same as Radio 1 (£40m), though less than Radio 2 (£46m).

The BBC's "Ten Pieces" has been an excellent initiative in taking classical music into primary schools, and soon to be followed up with a version for secondary schools. Will the BBC continue to provide 'early learning' in classical music on mainstream television and radio?

And will Radio 3 be allowed now to get on with its job of providing for dedicated, adult audiences - always allowing for a good children's programme (of the calibre of Pied Piper back in the 1970s)? Experience suggests that if it's any good, adults will profit from it too. -

March 2 2015: Not logical

- A few years ago Radio 3 launched a 'New Generation Thinkers' scheme to mirror the highly successful 'New Generation Artists' for young professional musicians. In the words of the Economic and Social Research Council:

The scheme wants to find the new generation of academics who can bring the best of the latest university research and scholarly ideas to a broad audience.

That is clear, good sense: there are enormously well informed young teachers and researchers who have a lot to give to the 'broad audience' outside the academic sphere. And how are they to do it? By leaving home territory, going out to the audience and presenting their material in an 'accessible' way.

What they don't do for this scheme is stand on the street corner in cool gear trying to persuade the public to enter home territory, the halls of Academia (where everything, have no fear, will be made simple and unintimidating for the 'broad audience'). That might do something for the few passers-by who accept their invitation - but it would do nothing for Academia, which would rightly face charges of 'dumbing down', a loss of reputation and a loss of intellectual credibility.

So thumbs up for the New Generation Thinkers, regardless of whether the innovative scheme pays dividends: it strengthens Radio 3's intellectual content and will meet with a receptive audience. Most importantly, Academia itself is left intact with all its rigour.

This is why it's illogical for Radio 3, which already is the radio station of choice for knowledgeable and dedicated listeners, to stand on the street corner in cool gear trying to persuade the public to come on in; and then oversimplify in order to be cuddly and accessible to the broad audience. Result? Radio 3 faces charges of 'dumbing down', a loss of reputation and a loss of intellectual credibility. Most importantly, Radio 3 is not left intact: it is ruined for existing listeners.

What's more, as a 'strategy' for introducing new listeners to classical music, it runs counter to what the BBC Trust required. As we have tirelessly pointed out, the Trust has stated (2011):

Radio 3 is the BBC's flagship service for making classical, jazz and world music available to licence fee payers. We note, however, that it is not the sole responsibility of Radio 3 to deliver the great works of classical music and other musical genres to all audiences. The BBC has an overall responsibility for this and there are many services with a role to play in achieving this ambition.

As the Trust said, other services are better placed than Radio 3 to do this: but a fat lot those other services are doing. Leading among them, we would point the accusing finger at Radio 2. In 2007, it scrapped its 'entry level' classical programme, Your Hundred Best Tunes, where many people say they first discovered classical music, and which led them on to Radio 3. It was ostensibly amalgamated with the somewhat lighter programme Melodies for You, and, a few months after the Trust's unambiguous statement, that was also scrapped.

Radio 2 still broadcasts Friday Night Is Music Night, but with barely a single item of classical music - and very little 'light orchestral' that isn't contemporary popular music. So, as far as BBC radio is concerned, Radio 3 shoulders the entire responsibility for introducing new listeners to the “great works of classical music”, amid tweets, texts, a bit of leavening from Ivor Novello, George Gershwin and Ronald Binge 'because it's breakfast time'. In short, the serious classical repertoire for serious listeners is gradually being eased into the margins of the furthest reaches of the BBC. Yes, of course there are bright spots - the 'good moments' - but the direction has been clear for years. Remember when BBC Two was the classy arts channel?

Surely someone at the BBC sees Radio 2's massive 15 million weekly audience as an indictment, a tribute to its supermarket musical blandness, rather than a token of the 'diversity' of its output? The radio consultant, John Myers, has said recently that Radio 2 is a “giant oil tanker” sailing in the wrong direction.

Is there no one taking the BBC shilling strong enough to challenge the present self-regarding, 'bums on seats' mentality of the corporation? Strong enough to urge that the serious arts are brought back into the mainstream? -

February 6 2015: Knowing when to laugh

- Supporters and others will know that we have been carrying out a survey of listeners' opinions on Radio 3, including their current listening habits. While being aware of many concerns, we wanted to discover what listeners liked, what they disliked and what they would like more of.

One point that emerged was that they appreciated a warm, intelligent sense of humour in a presenter, but were critical of flippancy and jokiness, where this suggested that the content 'wasn't being taken seriously'.

One context would be in discussing opera: a 'ridiculous' or 'absurd' plot doesn't mean that it is necessarily intended to be funny. Appreciating opera means suspending disbelief and engaging with the fundamentals: love, loss, sacrifice, suffering, grieving and - yes - comedy too.

Radio 3 appears lately to have been using, as its public face, people who seem to have neither appreciation nor knowledge of classical music, either regaling us with a facetious retelling of an operatic plot or trivialising what is moving, even tragic.

In the most 'heartbreaking moments of Doctor Who', people will experience them as they were intended, suspend their disbelief in a fantasy world, and feel for an isolated alien, in his love and loss. Oh, yes they do! (The evidence is on the internet). But transfer this to a Rameau opera - the djinn who falls in love with a human - and it becomes a jolly pantomime.

Then there's Facebook and Twitter. How much time is spent by Radio 3 employees on these little extras (our survey found that about 90% of our sample never looked at them)? But since they're there, promoting Radio 3, at least let it be done appropriately. How much time was spent expertly photoshopping a picture of Vaughan Williams to give him a bright red bobble hat and a football scarf, all wrapped up warm because we're about to play… the Sinfonia Antartica? Did anyone responsible for posting it on Twitter have the remotest notion that the work was inspired by, and followed events of, Scott's tragically ill-fated expedition to the South Pole? There are many more appropriate pictures to use. As Ursula Vaughan Williams wrote:

"He was excited by the demands which the setting of the film made on his invention, to find the musical equivalents for the physical sensations of ice, of wind blowing over the great, uninhabited desolation, of stubborn and impassible ridges of black and ice-covered rock, and to suggest man's endeavour to overcome the rigours of this bleak land and to match mortal spirit against elements."

So we'll put him in a red bobble hat and footie scarf. To represent the cold weather.

There just isn't a polite word to describe that. -

January 9 2015: How much?

- At a recent conference on public service broadcasting an ex-BBC (recently retired) media correspondent gave an interesting talk covering BBC radio. However, among his comments was the confident statement that two radio stations were “well-funded” - Radio 3 and Radio 4.

The BBC Trust now publishes, and regularly updates, the service licences - including guideline service budgets (i.e. allowable expenditure for each service).

Let’s look: for 2014/15 Radio 3 has a service budget of £40m, while Radio 1 has a budget of - £40m. So in what sense of the words “well-funded” is Radio 3 especially well-funded, and Radio 1 not? Further, Radio 2 has a budget of £46m; Radio 5 Live, having suffered the most drastic cuts over recent years, still has a budget of £50m. Radio 4 has £90m, which might well be termed, comparatively, very well-funded.

If you look back to the previous issue of the licences, 2013/14, Radio 1 had £41m. Radio 3 had £39m, so last year it was the outright worst-funded of the network stations: now it’s just the joint worst-funded.

More than that: consider the funding of the network stations’ digital sisters. Radio 1 has 1Xtra, which gets an added £6m, so a total of £46m for under-30s’ popular music. Radio 2 has 6Music, which gets £8m. That’s a total of £54m for popular music for 30+ listeners. Radio 4Extra gets £5m to add to Radio 4’s £90m, total £95m. And the part-time Sports Extra gets £2m, that’s £52m to add to 5 Live’s budget. But wait: Radio 3 gets a whopping… well, it doesn’t have a digital counterpart, so the budget for that audience segment remains at £40m. Again, in what sense does Radio 3 merit a special mention as being “well-funded”?

How about ‘cost per listener hour’? Mmmm. Think of it this way. A new production of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (broadcast time 2 hours 30 minutes): the actual cost to a station budget of that production will be the same, whether it’s heard by 100,000 listeners on Radio 3 (budget £40m) or half a million listeners on Radio 4 (budget £90m). The difference will be ‘cost per listener hour’ - five times higher for Radio 3 compared with Radio 4.

One other difference is that Radio 4 wouldn’t broadcast a complete Shakespeare drama over two and a half hours anyway (though it recently did Henry V in five episodes). But there presumably won’t be too many on Radio 3 either now, at something like £24,000 per broadcast hour for drama. And ‘cost per listener hour’ is a metric surely best left to cynical accountants who know the ‘price of everything and the value of nothing’.

Tuesday, 1 April 2025