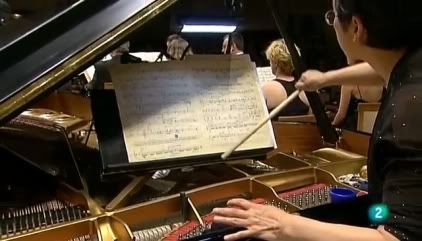

His "Double (Grido II)" - a strange name is it not for a thing that lasts almost half an hour - was put on in London not so long ago, but it may interest Members - especially those who were not present at that occasion - to see this video of a performance in Madrid. (Debussy's music for the "dance-poem" Games is included as well.)

(Or if that doesn't work try this longer one, which for some reason appears as it actually starts playing:

http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/l...hPcGVuPWZhbHNl )

Grido (whatever that may mean - if anything) is not at all my sort of thing, so I will confine myself here to only one comment: At one point we see a close-up of a string player drawing his bow not over the string, nor even over the muted string, but over the mute itself. I find this quite shocking, since any competent composer should be able to write sufficiently excellent music for ordinary instruments used in the ordinary way. And next they start tapping the wooden bodies of their instruments. The only reason I can think of for this sort of thing lies in the disturbed circumstances of the composer's childhood. Many Germans brought up in the course of that insane era seem - quite understandably of course - to have no sense of proportion or perspective. Stockhausen was just the same - and of the same generation.

Herr Lachenmann was present in the audience, but was not called up to the stage at the conclusion of the performance, nor even invited to rise in his place. He did applaud, but appeared to leave off his clapping long before the rest of the audience - which is I suppose only right.

More interesting was the behaviour of the performers. The conductor (a Herr Hermann) was kept very much on his toes - far too much I think, because he was obliged to concentrate upon beating time and giving cues to the detriment of everything else. As for the players (the RTVE Symphony Orchestra), they certainly did not smile, and may even have been hesitant, but since they are professionals it is difficult to tell. They wore much the same expressions during the second work, Debussy's Games.

Being a professional musician is a curious occupation is it not; one is remunerated for being both adept at the playing of anything that is set in front of one, but also for one's ability to be emotional about it. One's emotions must be evident but not one's preferences!

(Or if that doesn't work try this longer one, which for some reason appears as it actually starts playing:

http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/l...hPcGVuPWZhbHNl )

Grido (whatever that may mean - if anything) is not at all my sort of thing, so I will confine myself here to only one comment: At one point we see a close-up of a string player drawing his bow not over the string, nor even over the muted string, but over the mute itself. I find this quite shocking, since any competent composer should be able to write sufficiently excellent music for ordinary instruments used in the ordinary way. And next they start tapping the wooden bodies of their instruments. The only reason I can think of for this sort of thing lies in the disturbed circumstances of the composer's childhood. Many Germans brought up in the course of that insane era seem - quite understandably of course - to have no sense of proportion or perspective. Stockhausen was just the same - and of the same generation.

Herr Lachenmann was present in the audience, but was not called up to the stage at the conclusion of the performance, nor even invited to rise in his place. He did applaud, but appeared to leave off his clapping long before the rest of the audience - which is I suppose only right.

More interesting was the behaviour of the performers. The conductor (a Herr Hermann) was kept very much on his toes - far too much I think, because he was obliged to concentrate upon beating time and giving cues to the detriment of everything else. As for the players (the RTVE Symphony Orchestra), they certainly did not smile, and may even have been hesitant, but since they are professionals it is difficult to tell. They wore much the same expressions during the second work, Debussy's Games.

Being a professional musician is a curious occupation is it not; one is remunerated for being both adept at the playing of anything that is set in front of one, but also for one's ability to be emotional about it. One's emotions must be evident but not one's preferences!

on their instruments at the proms the other day

on their instruments at the proms the other day

.

.

Comment