Originally posted by ferneyhoughgeliebte

View Post

Colin Matthews (b1946)

Collapse

X

-

Interestingly, Schoenberg was once asked to elucidate on the 12-tone structure of his Violin Concerto, I think it was, and found himself unable to work out how its principles had been applied in a certain passage. Assuming this story is not apocryphal, one might venture to opine that the VC was an example of its composer breaking his own rules in the manner that would gain your approval; however, I understand that in the VC Schoenberg applied the 12-tone series pretty rigidly according to his own early principles of non-repetition, no octaves allowed, etc., which he was later to break or treat quite liberally in subsequent works; so I'm not sure whether this would back up your view on this matter, ferney, or accord to the way I manage to find something previously unnoticed almost every time I hear this magnificent work. I'm not too bothered about over-familiarisation, myself: re-playing Le Sacre in my head from memory actually does the same thing of uncovering previously unnoticed or unappreciated bits.

-

-

What we're talking about though isn't "breaking rules" as in disrupting the order of pitches in a twelve-tone composition, but intervening to disrupt processes in order to make them less predictable.Originally posted by Serial_Apologist View PostAssuming this story is not apocryphal, one might venture to opine that the VC was an example of its composer breaking his own rules in the manner that would gain your approval;

Surely many of those earlier "minimalist" pieces like Reich's Four Organs make a virtue of their predictability?

As for "knowing what's going to happen", once you get to know a piece you of course know what's going to happen however "unpredictable" the original experience was, right? Shouldn't this apply too to repeated sections in classical sonata movements - by your argument from predictability you presumably wouldn't want your Schubert repeats in place...?Last edited by Richard Barrett; 03-01-18, 09:29.

Comment

-

-

IndeedOriginally posted by Richard Barrett View PostWhat we're talking about though isn't "breaking rules" as in disrupting the order of pitches in a twelve-tone composition, but intervening to disrupt processes in order to make them less predictable.

Surely many of those earlier "minimalist" pieces like Reich's Four Organs make a virtue of their predictability?

Where would I am sitting in a room be without it?

There is a world of difference between being "pridictable" and being "boring" (though I quite like boring music)

when this starts

we know where it is "going" sonically BUT have no idea of where it will take us.

Comment

-

-

I hadn't heard that anecdote about the Violin Concerto, but there is a similar one about the Third Quartet - the famous occasion when Schönberg remarked that he found such "note counting" irrelevant, and that he was a "12-note composer, not a ... " bardy-balrdy-yakety-yak. Certainly from the evidence of his compositional sketches, and the "machines" he created to help him oversee the relationships between the various forms of the row, this was a public pose, owing more to his occult predilections (wanting to keep the "tricks of the trade" secret) than to his actual practice. It's ridiculous to imagine that the analyst who wrote so perceptively about Brahms, Mozart, Beethoven and others throughout his life was "unable to work out the principles" of a work that he had so meticulously sculpted - and whose "principles" are readily audible (it's what he does with those principles that's the point).Originally posted by Serial_Apologist View PostInterestingly, Schoenberg was once asked to elucidate on the 12-tone structure of his Violin Concerto, I think it was, and found himself unable to work out how its principles had been applied in a certain passage. Assuming this story is not apocryphal, one might venture to opine that the VC was an example of its composer breaking his own rules in the manner that would gain your approval; however, I understand that in the VC Schoenberg applied the 12-tone series pretty rigidly according to his own early principles of non-repetition, no octaves allowed, etc., which he was later to break or treat quite liberally in subsequent works; so I'm not sure whether this would back up your view on this matter, ferney, or accord to the way I manage to find something previously unnoticed almost every time I hear this magnificent work. I'm not too bothered about over-familiarisation, myself: re-playing Le Sacre in my head from memory actually does the same thing of uncovering previously unnoticed or unappreciated bits.

The Violin Concerto is quite a "late" work - the most important work on enriching the expressive powers of twelve-note composition had already been done in the Third Quartet, the Variations for orchestra, Moses & Aron, and the Op33 piano pieces - works whose richness of "grammar/vocabulary" (yer, I know - the Musical "equivalents" of these literary terms) goes far beyond the simplistic essay about the "rules" of "Composing With Twelve Notes Related Only to One Another" that he produced to shut up everyone who kept asking him what these "rules" were. If one uses that essay to try to follow Moses, you get stuck on bar two! They apply - if at all - only to the construction of a twelve-note series: the composition of the Music arises from the relationships both between the notes within that series (which is a Harmonic matter - that's what he emphasized in the "related only to one another") and between the various forms of the series. And, by the time he gets to the Violin Concerto, he's not "really" working with twelve-note series, but with two versions of a Hexachord - all this is why the Music features repetition, octaves etc, which the earlier (and, I think weaker) works such as the Wind Quintet avoid much more. ("Weaker", in my view, precisely because in those works the twelve-note process is more literal and predictable - the elaboration of the twelve-note process from Op 30 onwards is what makes for me a richer, more generous, more enigmatic Musical experience.)

I much prefer talking about Schönberg than about Matthews! Last edited by ferneyhoughgeliebte; 03-01-18, 12:21.[FONT=Comic Sans MS][I][B]Numquam Satis![/B][/I][/FONT]

Last edited by ferneyhoughgeliebte; 03-01-18, 12:21.[FONT=Comic Sans MS][I][B]Numquam Satis![/B][/I][/FONT]

Comment

-

-

But it's like a good joke (which you look forward to hearing no matter how many times you've previously heard it) as opposed to a predictable joke, that was never funny in the first place because you knew what the punchline was going to be. There is a psychological difference between experiencing something you already know well and the sort of "instantaneous predictability" of something that should be a new experience. And, with many works, the calibre of originality is so remarkable that each re-encounter reveals things not noticed before. The the richness of the expressive techniques of a work - and the way we change over the years - that keeps "re-freshening" it with each hearing. It sort-of recreates new areas of unpredictability by virtue of its already being "known".Originally posted by Richard Barrett View PostAs for "knowing what's going to happen", once you get to know a piece you of course know what's going to happen however "unpredictable" the original experience was, right?

(Logically, I don't think I can explain what all that means - it's just an impressionistic way of trying to explain why what I mean by the difference in experience of things that we/I "know" from those which we/I can "predict")

No - because structural repeats of the Classical period contain such great variety of "activity" within the process of Tonality (trans: "There's more going on between the repeat marks") than in the "reduced"/"concentrated" focus of those earlier "Minimalist" pieces. Schubert uses the Exposition to create and disrupt relationships of harmony and tonality have long-term implications that are only resolved at a moment of crisis and (at least partial) resolution - the "climax" of the Movement. Now, I know that there are some chaps here who like to get to Climax as quickly as possible, but the sense of timing depends on the repetition. An Exposition repeat is a different type of repetition from the short-term, literal repetitions that some processes require - not least because Expo repeats aren't (or shouldn't be) literal, but re-present material not heard for some time - and re-present it in the light of what has happened since the last time it was heard.Shouldn't this apply too to repeated sections in classical sonata movements - by your argument from predictability you presumably wouldn't want your Schubert repeats in place...?

Maybe there's a study suggested in all this - Seven Types of Predictability?[FONT=Comic Sans MS][I][B]Numquam Satis![/B][/I][/FONT]

Comment

-

-

Originally posted by MrGongGong View PostThere is a world of difference between being "pridictable" and being "boring" (though I quite like boring music)

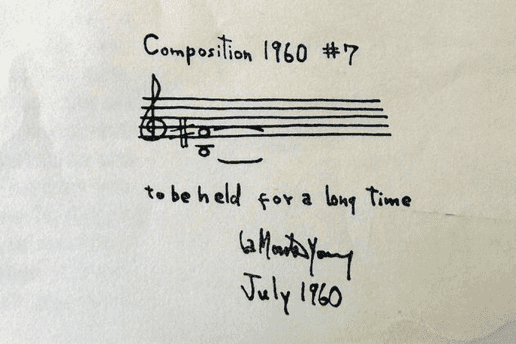

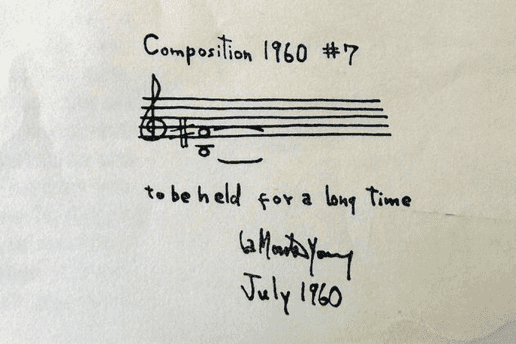

when this starts

we know where it is "going" sonically BUT have no idea of where it will take us. - but isn't that precisely what stops it from being "predictable"? It's a work I find "fits" my own preference for Music that establishes expectations and then disrupts them - in that (on the three occasions I've listened to it) the idea of holding an open fifth establishes a pattern, which is disrupted/contradicted/undermined by the various other sounds that start to "appear" the closer I listen.

- but isn't that precisely what stops it from being "predictable"? It's a work I find "fits" my own preference for Music that establishes expectations and then disrupts them - in that (on the three occasions I've listened to it) the idea of holding an open fifth establishes a pattern, which is disrupted/contradicted/undermined by the various other sounds that start to "appear" the closer I listen.

Of course, I realize that in all these word over my last few posts I'm just rationalizing the (probably) irrational reasons why I love or detest a work. (In the same way that you can never now say that you find DoG "boring"!)[FONT=Comic Sans MS][I][B]Numquam Satis![/B][/I][/FONT]

Comment

-

-

Except that there wouldn't necessarily be any disruptions, and that wouldn't affect the piece adversely. I've played it once, as part of an EBow electric guitar duo (together with a proper guitarist who has many deep links to the American experimental tradition). I played the B on an open string, and after a while started to get interested in doing a bit of subtle "undermining" by pulling the neck of the instrument backwards very slightly, which I indeed thought made everything sound much more interesting. However I was given a bollocking by my duo partner afterwards for completely missing the point.Originally posted by ferneyhoughgeliebte View PostMusic that establishes expectations and then disrupts them - in that (on the three occasions I've listened to it) the idea of holding an open fifth establishes a pattern, which is disrupted/contradicted/undermined by the various other sounds that start to "appear" the closer I listen.

I agree with you about repetition in Schubert et al. - but in intentionally predictable pieces such as the Young example or Four Organs or I am sitting in a room there is also always the matter of "in the light of what's happened in the meantime" - what you seem to be saying (and what I'm agreeing with) is that duration in itself is a facet of the musical material. Music like this could be seen as a "colouring of time" where predictability ceases to be a relevant concept.

However I woudn't have thought that Colin Matthews thinks in that way. He's clearly someone of wide and eclectic musical sympathies, and this is reflected in his music, but perhaps on the level of a tourist in these regions of differently expanded musical consciousness, who takes a few snapshots and then goes home rather than actually inhabiting them. But there's a lot of this kind of thing in British music.

Comment

-

-

Could you expand upon the means whereby you distinguish between composers responding to "wide and eclectic musical sympathies" "on the level of a tourist" and those doing so by "actually inhabiting them"? I understand the principle, of course, but I'm wondering how you identify and define that difference in relation to particular works.Originally posted by Richard Barrett View PostHowever I woudn't have thought that Colin Matthews thinks in that way. He's clearly someone of wide and eclectic musical sympathies, and this is reflected in his music, but perhaps on the level of a tourist in these regions of differently expanded musical consciousness, who takes a few snapshots and then goes home rather than actually inhabiting them. But there's a lot of this kind of thing in British music.

Comment

-

Comment