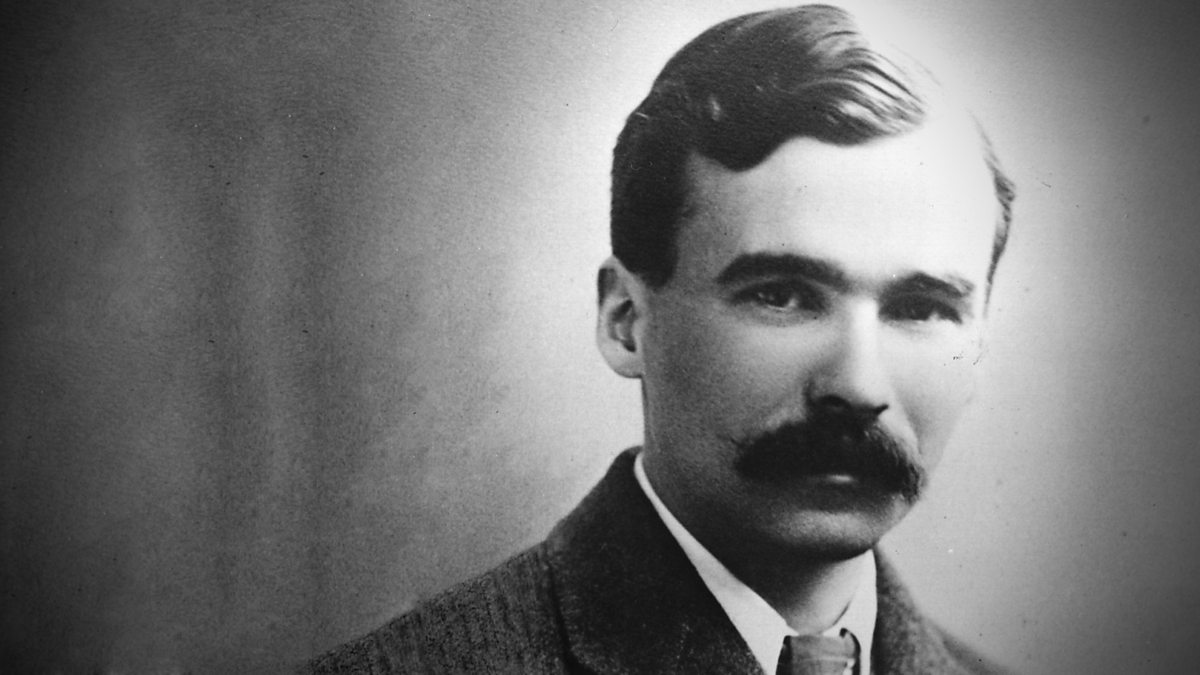

George Butterworth and contemporaries

Collapse

X

-

There's little out there S_A.Originally posted by Serial_Apologist View PostFarrar, Browne and Coles - names I've heard mentioned but whose music I have yet to hear; so yes, looking forward to this lot!

Don't know if these are still available,or on Spotify or some such

Just checked,the Farrar cd is in the Naxos library plus some songs by the other composers.

Pabmusic would be good on this thread,hope he's ok.Last edited by EdgeleyRob; 27-07-16, 20:45.

Comment

-

-

Thanks, ER; I'll check those out after listening next week.Originally posted by EdgeleyRob View PostThere's little out there S_A.

Don't know if these are still available,or on Spotify or some such

Just checked,the Farrar cd is in the Naxos library plus some songs by the other composers.

Pabmusic would be good on this thread,hope he's ok.

Yes it's been a long while since we've heard from Pabsy.

Comment

-

-

A word of warning about the Hyperion issue.Originally posted by Serial_Apologist View PostThanks, ER; I'll check those out after listening next week.

Yes it's been a long while since we've heard from Pabsy.

The 2CD dyad set (itself a reissue) seems to be available via their archive service.

There is now a single CD issue, also (confusingly) called War's Embers:

The contents differ from those of the originals that made up the dyad set, but some of the Farrar settings are included.

Comment

-

-

Hello everyone. I saw my name (Pabsy?!!) in various comments and thought I’d join in. I’m having major computer problems that can’t be fixed before the end of August, so I’m using Mrs Pab’s iPhone and a file sharing app to write this.

Here’s some notes I recently sent a friend who’s preparing a talk (with music, hence the cues). You might find it interesting. This is the first of two or three posts (the original is too long).

We’re familiar with writers, poets and artists who were examples of the tragedy of war or commentators on it. Well, that is no less true of composers, and the Great War affected 20th-Century music as much as it did any other of the Arts.

Their stories often mirror the tragedy of the war, sometimes in small ways; often in big ways.

One musical disaster happened in July 1914 and suggests how little Britain expected a war. Ralph Vaughan Williams posted the only score of his new London Symphony to publishers in Leipzig for engraving. It disappeared in the confusion of the outbreak of war and it was only the devotion of friends, who reconstructed a new score from the orchestral parts, that ensured one of the most popular symphonies of the century was preserved. Leader of the group of friends was a 29-year-old composer called George Butterworth who we will meet again.

[Magnard] Music 1

But losing your only score is nothing compared with losing your life – especially so when you are a civilian. Albéric Magnard was a 49-year-old who lived in Alsace. He had achieved recognition with three operas and four symphonies and with his Hymne à la Justice in support of Alfred Dreyfus. At the outbreak of war, he sent his wife and daughters to safety while he stayed behind to safeguard his home at Baron, Oise. A troop of Uhlans entered his grounds on 3 September 1914, and Magnard fired at them, killing one. They in turn set fire to the house and Magnard died in the fire. The only score of his last opera was destroyed as well.

[Granados] Music 2 or 2a

Magnard was not the only civilian composer to die in the war. Most famous was probably another 49-year-old, Enrique Granados from neutral Spain. He was a noted pianist who was well known for his piano works, especially Goyescas based on the paintings of Goya. He expanded Goyescas into an opera, whose first performance was delayed by the outbreak of war. It was eventually premiered at the Met in New York in 1916. It was while Granados was returning from this that his ship, SS Sussex, was sunk in the English Channel.

But there were many young composers who lost their lives fighting on different fronts. One problem with dying young is that there’s often only a hint left behind of future possibilities, but two of them at least had begun to establish reputations and might well have gone on to greater things had they survived.

[Stephan] Music 3

Rudi Stephan came from Worms in Hesse. He was influenced by German Expressionism and gave his compositions prosaic titles, such as Music for Orchestra (1910) or Music for Violin and Orchestra. He completed an opera, Die Ersten Menschen, shortly after the war started. He volunteered in 1914 and was killed by a Russian sniper near Tarnopol on the Galician front on 29 September 1915, just two days after he had arrived there. His body was never recovered. His music had to wait until recent years before it was recorded and programmed fairly regularly. There are some indicators in his works that if he had lived he could have created a third musical style in between the cerebral music of Berg and Webern on the one hand and the emotional music Richard Strauss or Korngold on the other.

[Butterworth] Music 4, 5 or 6

Perhaps the best-known musical loss of the war was Acting Lt. George Sainton Kaye-Butterworth of the Durham Light Infantry, whom we met earlier recovering Vaughan Williams’s London Symphony and who was known just as George Butterworth in his musical life. Like other British musicians at the time, he had been influenced both by the dying traditions of folk song and dance, and he was at one time a professional folk dancer. The poetry of A. E. Housman was also very influential and he had already made an impression with his song-cycle Six Songs From “A Shropshire Lad”, his orchestral Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad, and the miniature tone poem The Banks of Green Willow before he volunteered for the war.

He kept an entertaining and perceptive War Diary that engagingly covers many of the everyday things British and Commonwealth forces endured on the Western Front. If anything it demonstrates the degree of confusion that existed throughout. Here is his account of leading a patrol into no-man’s-land at night in October 1915. Two soldiers sent out to harass the enemy snipers had failed to return, and Butterworth was put in charge of a search party:

We filed out (about 16 strong) by the usual exit, myself in the rear, according to instructions. When first clear of our wire everyone suddenly lay down, and at the same time I heard a noise in a tree just to our left. Feeling sure that it was a man I got hold of a bomber, and together we stalked up to the tree. I then challenged softly, and no answer being given, the bomber hurled his bomb, which went off in great style. It struck me afterwards that it was foolish to give ourselves away so early in the proceedings, but I am narrating this as an example of how not to conduct a patrol. After satisfying ourselves that there had never been anyone there, we rejoined the others, and I passed up the order to advance. After ten yards crawling everyone lay down again, and this went on for about half-an-hour. By this time I was getting tired – also wet, and as we only had a limited time at our disposal, I decided to go up to the front – instructions notwithstanding – and push on a bit faster … so we went forward about 150 yards without meeting anything, and as time was short, I decided to circle round by a different route to our starting point. By this time everyone had acquired a certain degree of confidence – seeing that not one shot had been fired in out direction – and the last part of our journey was carried out at a brisk walk, and without any attempt at concealment …The two missing men turned up in the morning.

In his brief career at the front during the battle of the Somme he was “mentioned in dispatches”, recommended for the Military Cross for his actions on July 9th (it was not awarded, though), awarded the Military Cross for his bravery on July 16-17th, and – according to his commanding officer – did enough on the night he died to have won the MC again but in those days it was not given posthumously. One of the more unusual things was that Butterworth never spoke to anyone in the Army about his music, nor did he tell his father that he had won the MC. Butterworth was shot by a sniper while defending a captured trench near Pozières in the early hours of August 5th 1916. His body was never recovered.

Butterworth’s music has never been out of the repertoire, at least not in Britain and the USA. This is perhaps in part because of his Housman songs, and especially "The lads in their hundreds", which poignantly tells of young men who leave their homeland to “die in their glory and never be old”.Last edited by Pabmusic; 30-07-16, 09:04.

Comment

-

-

And the second part:

[Kelly] Music 7 or 7a

Born in Australia, 35-year-old Frederick Septimus Kelly attended school and university in Britain. At Oxford he became a keen rower, eventually winning a gold medal at the 1908 Olympic Games in London. He was also a formidable concert pianist. His compositions were not that many, but the orchestral Elegy: In Memoriam Rupert Brooke is a profound tribute to his friend, the poet who died of blood poisoning whilst Kelly and he were travelling to Gallipoli with the Royal Naval Division. Kelly was one on the burial party who interred Brooke on the island of Skyros; the Elegy is an almost unbearable memory of this. It is one of the very few pieces composed on active service – Kelly began it as he sat at the bedside of the dying Rupert Brooke and finished it as he was recovering in Alexandria from his wounds. Although he was wounded twice, Kelly survived Gallipoli (winning the DSC) only to die attacking a machine gun emplacement in the final days of the Somme on November 13th, 1916.

[Browne] Music 8

The 26-year-old William Denis Browne was also one of Rupert Brooke’s burial party. They had attended Rugby School and Cambridge together. A fine pianist, Browne gave the British premiere of Alban Berg’s Piano Sonata. His compositions amount to a handful of songs, some choral pieces and some unfinished orchestral works. However, they do include one song – To Gratiana Dancing and Singing – that has been called one of the six greatest songs in English. Browne had to be left behind when he was severely wounded on June 4th 1915, during the third battle of Krythia; his body was never recovered.

[Coles]

Cecil Coles was a Scot who was killed by a sniper while Coles was burying the dead in Picardy on April 26th 1918. A friend of Gustav Holst, Coles composed two movements of an orchestral suite Behind The Lines whilst serving at the front, sending the music – mud-stained – to Holst in England, who preserved it. Holst himself dedicated his 1919 Ode to Death to Cecil Coles and all the other musicians who had died.

There were also composers who survived, but whose lives were irreparably damaged. Best-known are probably Ivor Gurney and E. J. (“Jack”) Moeran.

[Gurney]

Ivor Gurney was not only a composer: he was a major poet as well. In 1917 he was wounded and later gassed before succumbing in 1918 to shell shock. He recovered intermittently but deteriorated, eventually being declared insane in 1922. He spent the last 15 years of his life in mental hospitals, making more than one attempt at suicide. During these years he wrote eight collections of poetry and two plays. His music consists mainly of songs – more than 60 of them, staple fare for any singer of English song – but oddly enough only once did he set one of his own poems to music.

[Moeran]

Jack Moeran was an Anglo-Irish composer who served as a dispatch rider during the war. He was severely wounded at Bellucourt in 1917 and had a metal plate inserted in his skull. His musical output was notable, including a fine symphony (1934-7), a violin concerto (1942) and a cello concerto (1945), which are all regularly played. He began drinking heavily in the 1920s becoming eventually an alcoholic, a condition made much worse by his war wound. He was found dead in a river in Ireland in 1950 having suffered a brain haemorrhage.

[Vaughan Williams]

Ralph Vaughan Williams volunteered in 1914 (even though he was over-age – he was 42) and served as a medical orderly and later as an Artillery officer. His Pastoral Symphony of 1922 paints a surreal picture: “It’s really wartime music – a great deal of it incubated when I used to go up night after night in the ambulance wagon at Ecoivres and we went up a steep hill and there was wonderful Corot-like landscape in the sunset”. There is no doubt that he was deeply affected by the loss of many friends, especially George Butterworth.

[Holst]

Vaughan Williams’s close friend Gustav Holst was English, his father’s family had Estonian, German and Swedish roots. Gustav’s full name was actually Gustavus Theodore von Holst; that changed in 1916 when he began to call himself the name by which he is remembered. The autograph full score of The Planets – written between 1914 and 1916 – has each movement except one signed ‘Gustav von Holst’. The last to be written, Mercury, is signed ‘Gustav Holst’.

Holst tried to enlist but was medically unfit. Nevertheless, he went to Salonica in 1918 with the YMCA, immediately after the first performance of The Planets.

[Ravel] Music 9

A friend of both Vaughan Williams and Holst, Maurice Ravel joined the Thirteenth Artillery Regiment of the French army at the age of 40, and served as a truck driver throughout the war. In the decade that followed, his output (which was never prolific) declined and this is generally put down in part to what we now call PTSD – delayed shell shock, in other words. His legacy from the war was the suite Le Tombeau de Couperin, a piano work (later orchestrated) with each movement dedicated to a friend who had died, most of them at Verdun.

In 1929 Ravel wrote his Piano Concerto for the Left Hand for Paul Wittgenstein, the Austrian pianist (and brother of Ludwig the philosopher) who had lost his right arm fighting the Russians in Galicia.

[Rachmaninoff]

Although he did not fight, the aristocratic Sergei Rachmaninoff was a direct victim of the Russian Revolution, his estate confiscated and his having to flee to the USA, never seeing his family again.

[Elgar] Music 10**

Edward Elgar was 57 when the war began. His fame had come largely with the support of German musicians: he loved Germany and could not believe Britain and Germany were at war. There was a distinct decline in his popularity at home, while his music was no longer played in Germany. When someone asked at a concert with a small audience “Where are Elgar’s friends?” the conductor Thomas Beecham replied “They’re all interned”. Although he wrote some fundraising works for Belgian and Polish refugees, and a stage review with Rudyard Kipling called The Fringes of The Fleet (which contains an eerie setting of a poem called Submarines – “and the mirth of a seaport dies when their blow strikes home”) much of his wartime music was a retreat into childhood, with the stage works about fairyland, such as The Starlight Express and the Sanguine Fan. In 1917 he began to write chamber music in a cottage in Sussex from where he could hear the big guns of the 1918 Spring Offensive across the Channel. He ended the war a weary and resigned man, as witness the despairing Cello Concerto of the same period. Although he lived another 16 years (and was appointed Master of the King’s Music) he never wrote any more major works.

** Elgar was the first composer to take gramophone recording seriously. From January 1914 for almost 20 years to the day, he recorded most of his orchestral music (his output fits on 20 CDs) including highlights from The Starlight Express. These records, made in February 1916 featured Charles Mott, the singer who had made a success of the music on stage. He was to die in May 1918 of wounds received in Picardy. At least one of the records reached the front lines for Elgar received a letter from a Captain at the Front in 1917:

Though unknown to you, I feel I must write to you to-night. We possess a fairly good Gramophone in our Mess, and I have bought your record Starlight Express: ‘Hearts must be soft-shiny dressed’ being played for the twelfth time over. The Gramophone was anathema to me before this war, because it was abused so much. But all this is changed now, and it is the only means of bringing back to us the days that are gone, and helping one through the ‘Ivory Gate’ that leads to Fairyland, or Heaven, whatever one likes to call it. And it is a curious thing, even those who go only for Ragtime revues, all care for your music … Music is all that we have to help us carry on.

The War Memorial at the Royal College of Music in London lists the names of 38 former students who died in the war. It is a scene repeated in music academies across much of the world. Many name all their students who died, irrespective of nationality, emphasising that they had all been united by the universal language of music.

Comment

-

-

Elgar's war music is largely forgotten, though The Spirit of England is quite a major work. But the one that I consider to be a real gem is the recitation A Voice in the Desert, which also includes a soprano soloist. Those who accuse Elgar of jingoism should hear this.Originally posted by Pabmusic View PostEdward Elgar was 57 when the war began. His fame had come largely with the support of German musicians: he loved Germany and could not believe Britain and Germany were at war. There was a distinct decline in his popularity at home, while his music was no longer played in Germany. When someone asked at a concert with a small audience “Where are Elgar’s friends?” the conductor Thomas Beecham replied “They’re all interned”. Although he wrote some fundraising works for Belgian and Polish refugees, and a stage review with Rudyard Kipling called The Fringes of The Fleet (which contains an eerie setting of a poem called Submarines – “and the mirth of a seaport dies when their blow strikes home”) much of his wartime music was a retreat into childhood, with the stage works about fairyland, such as The Starlight Express and the Sanguine Fan. In 1917 he began to write chamber music in a cottage in Sussex from where he could hear the big guns of the 1918 Spring Offensive across the Channel. He ended the war a weary and resigned man, as witness the despairing Cello Concerto of the same period. Although he lived another 16 years (and was appointed Master of the King’s Music) he never wrote any more major works.

** Elgar was the first composer to take gramophone recording seriously. From January 1914 for almost 20 years to the day, he recorded most of his orchestral music (his output fits on 20 CDs) including highlights from The Starlight Express. These records, made in February 1916 featured Charles Mott, the singer who had made a success of the music on stage.

Comment

-

-

Huge thanks from me too, "Pabsy"Originally posted by antongould View PostWonderful "pabsy" thanks ever so much for that .... a lot I didn't know. I have just listened yesterday on Apple Music to a CD featuring works by Stephan, Butterworth and Coles and I'd, shamefully, never heard of Stephan. Very much looking forward to the COTW ......

To reproduce all those details on an iphone would have demanded a lot of effort, and I'm sorry to hear of your computer problems.

To reproduce all those details on an iphone would have demanded a lot of effort, and I'm sorry to hear of your computer problems.

I note that "To Gratiana Dancing and Singing" by Denis Browne forms part of Tuesday's programme, probably coming on pretty early in the programme.

Comment

-

-

Originally posted by Eine Alpensinfonie View PostElgar's war music is largely forgotten, though The Spirit of England is quite a major work. But the one that I consider to be a real gem is the recitation A Voice in the Desert, which also includes a soprano soloist. Those who accuse Elgar of jingoism should hear this.

Comment

-

Comment