The tierce de picardie seems to me to be a strange musical device - popular in the late Rennaissance and Baroque eras. The idea of ending a work or movement in a minor key with a major chord seems insensitive at the very least, and can be destructive of the mood of what has gone before.

Various reasons have been given inits defence:

"A strong ending" is one. I'm reminded of Salieri's comment in Amadeus: "You didn't even even give them a loud chord at the end to tell them where to clap."

"Minor chords have major harmonics that clash, so ending with a minor chord is less satisfactory."

(Yer what?)

Let me explain:

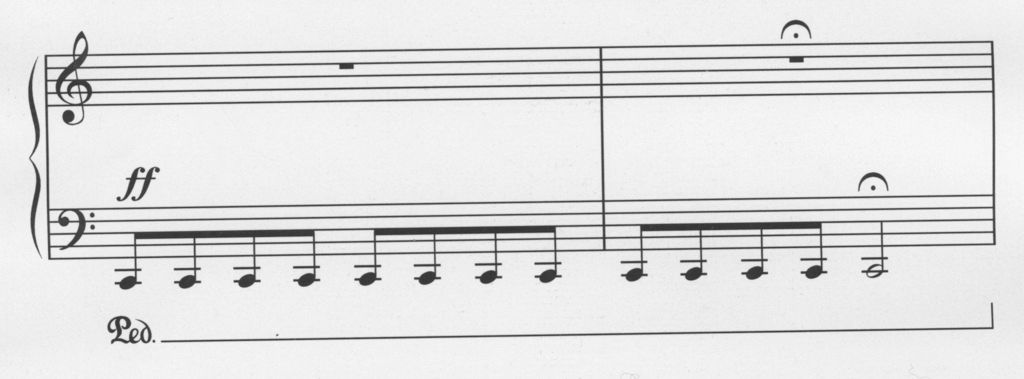

You'll need a piano that's in tune (and it won't work on an electric one). Hold down the sustaining pedal and thump out a series of low Cs (and don't release the pedal).

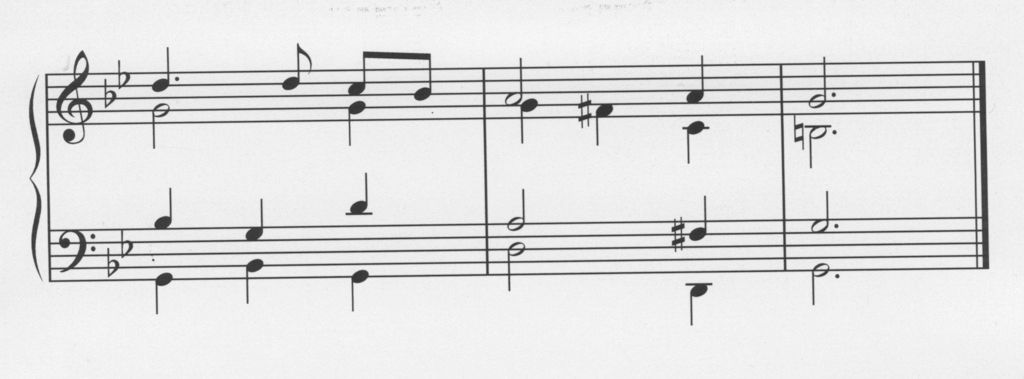

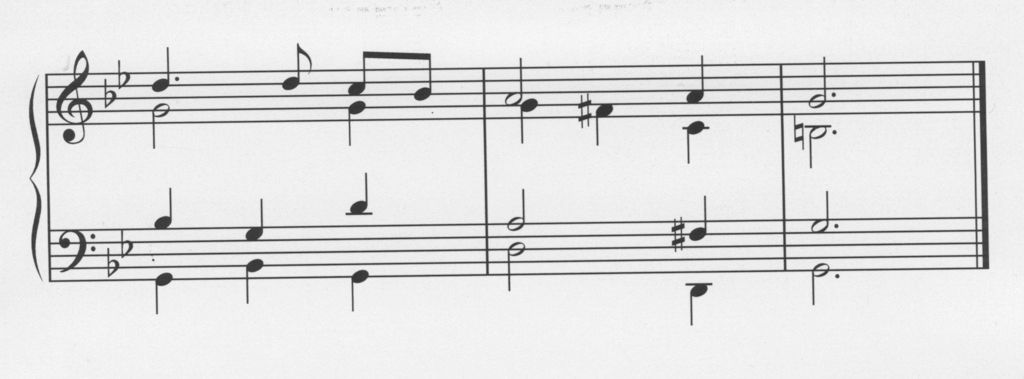

The harmonics will be heard for this chord:

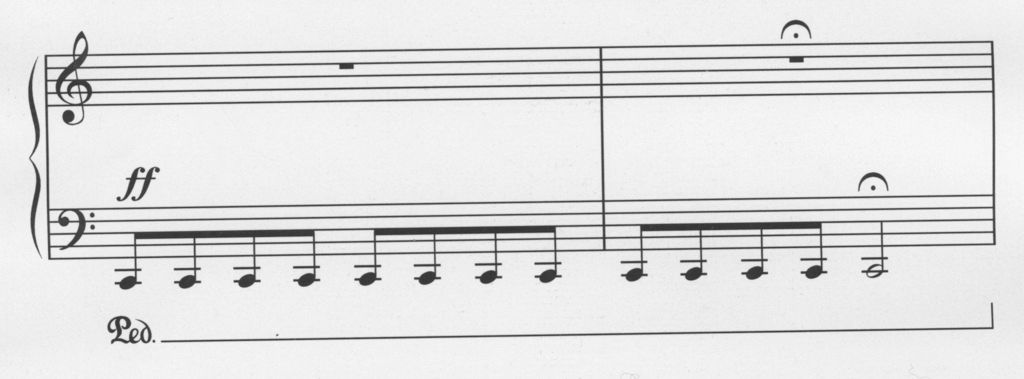

and especially the E:

Some theoreticians maintain that this will clash with the E flat of a C minor chord. Hmm.

Personally, I just despair that Bach could compose the most magnificent fugue ever to open his B minor Mass, and then destroy the mood so viciously by ending with a major chord.

Just occasionally it can work. Act III of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake concludes with Odile revealing her true self, and the sudden switch to the major key at the end emphasises the devastating hurt that Prince Siegfried is feeling.

Various reasons have been given inits defence:

"A strong ending" is one. I'm reminded of Salieri's comment in Amadeus: "You didn't even even give them a loud chord at the end to tell them where to clap."

"Minor chords have major harmonics that clash, so ending with a minor chord is less satisfactory."

(Yer what?)

Let me explain:

You'll need a piano that's in tune (and it won't work on an electric one). Hold down the sustaining pedal and thump out a series of low Cs (and don't release the pedal).

The harmonics will be heard for this chord:

and especially the E:

Some theoreticians maintain that this will clash with the E flat of a C minor chord. Hmm.

Personally, I just despair that Bach could compose the most magnificent fugue ever to open his B minor Mass, and then destroy the mood so viciously by ending with a major chord.

Just occasionally it can work. Act III of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake concludes with Odile revealing her true self, and the sudden switch to the major key at the end emphasises the devastating hurt that Prince Siegfried is feeling.

in a discussion like this, but noticing the title... didn't Hans Keller make a point of mentioning Schoenberg's use of the tierce de picardie, at the end of his 2nd String Quartet? It might have been in "Music 1975"**...

in a discussion like this, but noticing the title... didn't Hans Keller make a point of mentioning Schoenberg's use of the tierce de picardie, at the end of his 2nd String Quartet? It might have been in "Music 1975"**...

Comment